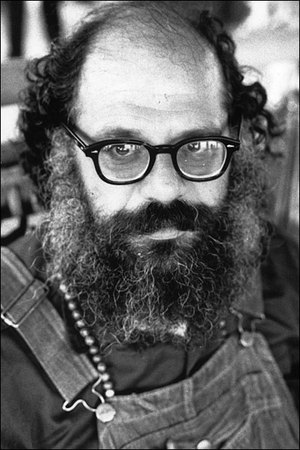

Allen Ginsberg's voice into my brain today. Over and over I keep listening to "I am I, old Father Fisheye that begat the ocean" and so on for four or so lines, then I skip ahead to the finale of the same poem—"The End"—over and over, "come Poet shut up eat my word, and taste my mouth in your ear." I can't get rid of it—the rhythm of the language, the performance of the poem, the hiply odd imagery.

Allen Ginsberg's voice into my brain today. Over and over I keep listening to "I am I, old Father Fisheye that begat the ocean" and so on for four or so lines, then I skip ahead to the finale of the same poem—"The End"—over and over, "come Poet shut up eat my word, and taste my mouth in your ear." I can't get rid of it—the rhythm of the language, the performance of the poem, the hiply odd imagery.So I'm breaking form. Instead of quixplicating a contemporary poem by a likely still living poet, I'm jotting down some thoughts on "The End." And, because I can't find a reliable version of the poem on the net, I'm including it here (I don't normally reprint) as it appears in my copy of Ginsberg's Selected Poems 1947-1995, originally from Kaddish and Other Poems (1961). Somewhere along the line I also acquired an audio version of it (probably from the aforementioned Mark Campbell). Listen from another tab as you read "The End" (Allen Ginsberg):

The End

I am I, old Father Fisheye that begat the ocean, the worm at my own ear, the serpent turning around a tree,

I sit in the mind of the oak and hide in the rose, I know if any wake up, none but my death,

come to me bodies, come to me prophecies, come all foreboding, come spirits and visions,

I receive all, I’ll die of cancer, I enter the coffin, forever, I close my eye, I disappear,

I fall on myself in winter snow, I roll in a great wheel through rain, I watch fuckers in convulsion,

car screech, furies groaning their basso music, memory fading in the brain, men imitating dogs,

I delight in a woman’s belly, youth stretching his breasts and thighs to sex, the cock sprung inward,

gassing its seed on the lips of Yin, the beasts dance in Siam, they sing opera in Moscow,

my boys yearn at dusk on stoops, I enter New York, I play my jazz on a Chicago Harpsichord,

Love that bore me I bear back to my Origin with no loss, I gloat over the vomiter

thrilled with my deathlessness, thrilled with this endlessness I dice and bury,

come Poet shut up eat my word, and taste my mouth in your ear.

One of the things I enjoy about "The End" is what I enjoy about a lot of Ginsberg's poetry: his performance of it. Too often I've been to a reading in which the fabulous on-the-page poet has bored me and much of the rest of the audience to yawns if not tears. Such a shame! One way or another, poems should be sung, and Ginsberg sung his well. The timbre of his voice unattractive but unique, and he reads with emotion and energy, two necessary traits too often lacking at a poetry reading—slam aside. Nothing better than a poet who knows how to read a poem—nothing worse than poets who read as though the audience isn't even present. For whom are they there?

I think, too, "The End" is a fair example of Ginsberg's aesthetics in general: the litany, the all-encompassing, the self-indulgent, the sexual, the visceral, the surreal, the Biblical cadences he co-opted from Whitman (among the other things he co-opted from Whitman and many others), the quasi-sloppiness. It's all there. Among my favorite moments is the poem's opening line, "I am I, old Father Fisheye that begat the ocean, the worm at my own ear, the serpent turning around a tree" and, of course, the closing line, "come poet shut up eat my word, and taste my mouth in your ear." Not only is the language raw and punchy and the rhythm riff-like with its spondee repetitions, but the image of the "ear" helps the poem arrive full circle. Notice how it's "my own ear" in line 1 but "your ear" in the last line. The poem's a Möbius strip.

I don't often think of Ginsberg's poetry as persona poetry, but I've always thought the "I" in "The End," the poem's speaker, wasn't Ginsberg. Who is "old Father Fisheye"? God? Death? Truly—it's Allan? I read the "Father" as some sort of Universal Mind figure, perhaps a reference to the Buddhist concept of Anatman, perhaps an amalgam of all the above. I don't believe it matters too much that we know exactly who the "Father" is, only that we know his vision is wide—like a fisheye lens. In this regard, the speaker is Allan Ginsberg, but only by default of the Anatman-like quality of the "I" in the poem. Ginsberg is one of the speaker's many selves. As he says, "I receive all." I've heard others discuss the speaker as Death, the end with a capital E, but there are too many beginnings in the poem for such a reading. "I delight in a woman's belly" makes me think of a pregnant woman, for example, the words "delight" and "belly" bearing several meaning's here. More likely the poem utilizes the cycle of life and death, the process of each occurring simultaneously such that one is not separate from the other but the other in a different form. Not sure if that makes sense, exactly... but the cycle, the simultaneity, runs throughout the poem as a central theme.

As such, I find the poem ironic. It isn't really "The End" at all, nor is it the beginning. And, assuming the speaker is not Allen Ginsberg but Allen Ginsberg assuming the voice of Father Fisheye, the poem is a call to the poet to shut up and listen for once. Ginsberg, as passionate as he was erudite, was no stranger to verbosity, yet here his speaker is telling him—the great "Poet"—to be quiet for a second, to meditate. This is appropriate given that "The End" is the last poem in Kaddish and Other Poems, a 100-or-so page collection titled after Ginsberg's "Kaddish," concerning the life and death of his mother. The story goes that Kaddish—a Jewish prayer given for the dead—wasn't recited at Ginsberg's mother's funeral. He wrestles with this fact for like two years, finally discusses it with friends, visits his mom's grave for the belated prayer, and shortly thereafter out comes the poem—something like that. So, 100 pages later, enough already. Perhaps that's a general call for enough already (although Ginsberg would go on to write a great free-for-all of poetry).

Ginsberg was one of the first poets I really fell in love with. I think I fell in love with all the first poets I read, actually, but my buddy Mark Campbell was something of a scholar of the Beats, and likely with his instigation Ginsberg has remained a favorite a mine while many of the others have come and gone. Strangely, as fresh as I find his language and style, I can't help but feel it's equally dated. Not so long ago I wrote about the "self" in poetry, prompted by the thoughts of poet Cam Scott (among other poets—the issue of the self in poetry not a twenty-first century dilemma). The common consensus is that too much me is a bad thing for poetry, a shunned thing even, but cripes—there's a lot of self-indulgent "I" in "The End," regardless of who it is or isn't. And that emphatic tone? It happens, but more often contemporary poetry's tone tends to the distant, the stoic, the monotone, the ... unemotional, though the content of the piece may be rather moving. We seem to have a distrust of language at that emotional level, the lingering effects, perhaps, of Language Poetry, more directly of disassociation and the intentional breaking of meaning and feeling.

Ginsberg never had problems with either one of those. In fact, often his poems come at you like a train, like the squeal of a sax, like he sung them via the technique of circular breathing. Always a success? No. But often worth listening to.

No comments:

Post a Comment