Saturday, November 19, 2011

Elton Glaser's "Downloading the Meltdown"

"Downloading the Meltdown" is a twelve-line poem made of six couplets, each line say 5-7 stresses in length, so mid-to-longish. You can tell from his title that Glaser enjoys sound-play with his use of "Down," that he has and uses an awareness of how his words fit together, play against and with each other. Such play here isn't...subtle. It isn't heavy-handed exactly, but it is meant to be heard (and seen, I suppose). In poetry's current age of disassociation and quasi-unconsciousness, this seems to be a decision Glaser has made in "Downloading" instead of the effect of the random positioning of verbage and its various accoutrement. As a craft element, this sense of decision-making is one of the things I look for in a poem of any variety of poetry. It's what separates art from the mere gathering of its materials.

Glaser employs a good deal of sound device throughout "Downloading," which grants the poem a consistent aural texture. Most often I hear consonance, as in these phrases from lines 1 and 2 respectively, "low and pink" and "summer slack," the d's from line 3, the more subtly used l's of the first three stanzas, and so on. In any given stanza, there's music to be heard. Particularly I like his rhythmic repetitions. Although I would not consider "Downloading" metrical, nor rhythmic in its meditation, there is a punchy phrase repeated throughout, almost like the tonic of a musical scale, that returns the reader's ear to homebase. I like this device because as the poem's images progress, as the narrative progresses, the repetition of this acoustic phrase keeps me (re)focused on the material at hand. Often in poetry this is done with the repetition of an image, which is fine, but such sound-play is a bit trickier and, therefore, laudable in a way that the echo of an image is not. Plus, an image can bear with it a heap of meanings that, typically, a rhythm cannot do. A heart, a cross, a raven, for example. I don't think an iamb, even with its rich tradition, comes to symbolize any comparable list of ideas and notions as so many of our images do, including the aforementioned. I say cross, and everyone arrives at the same shortlist of thoughts and images. I say iamb, and we poets may think of meter, sonnets, Shakespeare as being associated with the iamb, but not represented by it. It's just not the same.

Anyway, as I was saying, Glaser uses a rhythmic trigger throughout the poem as a binding device, as can be heard in the last phrases of his poem's first line: "low and pink." This is echoed in the succeeding two lines with "summer slack" and "case of slow" respectively. And this continues until the poem's ultimate line and final phrase, "odds and ends." The penultimate line finishes with "smoke and rum." There's just too many instances here to say the repetitions of the amphimacer (that's stressed-unstressed-stressed) are an accident. Yet, they are built with a variety of scaffolds such that the stress pattern surrounding each repetition is different. Thus, the poem isn't metrical and never feels that way. The repetitions don't sound stilted. They're sound savvy. Similar repetitions occur within single lines, sometimes by way of the amphimacer, sometimes in the fashion of the poem's title, sometimes of another sound device. The phrase "the hot night, the moon cool" from line 10 is like that, sort of an ironic twist of the language and two spondees back to back—two bacchics, really.

Glaser's images are tight, too, though I don't enjoy them as much as I do his sounds. Lines like "Depressed as a backdoor detective on a case of slow clues" are silly to me. They are nevertheless specific and interestingly worded. The diction isn't slack here, and it does the poem and its readers justice by continually offering us something to look at or think about. There's no fluff, no sagging, and I like all the little Catholic nods, as they torque up the tension quite a bit. If this was just about a guy sitting on his back porch watching the sunset "through a haze of smoke and rum," well, I've read that one before. Probably I've written my own version of that several too many times. But the idea of choirboys and bishop's boudoirs drops the poem into a much wider horizon of possibility. I mean—who is this guy? And why is he in a state of "What's left of me"? Are we talking about a sunset, or a son-set? (whatever that is exactly) I leave that for somebody else to decide.

Friday, November 11, 2011

Two Poems for Veterans Day

Homecoming

-originally published in Red River Review

I walk in the closed cavity

of myself, glancing up

the alley behind Jigs’, the one tavern,

the True Value store, the feed lot,

the grunts amid the heaps,

the flies.

Nothing’s changed. Maggots

flies flies maggots, angels

descend upon the living and the dead.

What I’ve found here, what calls me here

is a winged, terrible thing, its red mouth

sucking me in secret. With a lift of my foot

I am gone, deep in the war

as if in prayer.

Those Nights In L.A.

-originally published in Triplopia

Nothing but laughter those nights

after we closed the studio

and some of us took the Ten to Ocean Avenue

for a stroll along the beach. Others

drove home to wives, families, the six o’clock news

setting the war down in their living rooms

like a guest who would overstay his visit.

But in the Blue Room, we’d laugh and laugh,

nothing could hurt us. Shots

ran through us like water on hottest days,

and our big mouths roared over small jokes

at the other poor bastards in the world, the fucked up

moments of their lives a cacophony of booze,

Angels’ games, Hendrix, white noise

we romped around on like teenaged children

who’d eaten their virgin to her core, juice

spilling over our lips, and the world crumbling into an emptiness

that grew as silence grows, quietly, tenderly,

to take our breath away. Those nights

I heard boys in other rooms of our house.

I saw their bodies straighten like reeds along a river

then flatten beside us in the paddy.

An awful wind passed.

I was there when Gale Sweet drug his rag across the empty stools

and unplugged the box, but still

the sound of a thunder, ten thousand whispering

and the walls alive, and the television

flashing through the dark like light through the limbs of trees

though I wouldn’t move, wouldn’t make a sound. When sweat dropped

to my thigh with a soft puussssh, I leaned closer. Behind the door,

irregularly, my wife breathed. I closed my eyes.

One inch, then another, breath for breath, I slid away

as though gliding under water, the moon above me, the stars.

In the halogen glow of my garage, jug in hand, I heard her

nice and steady,

then poured life through me like a river.

Thursday, November 3, 2011

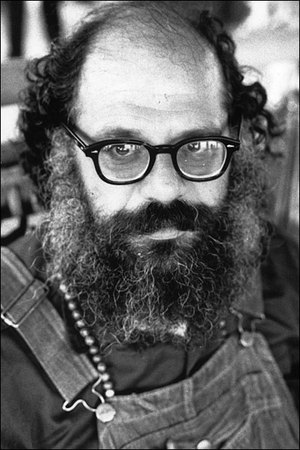

Allen Ginsberg's "The End"

Allen Ginsberg's voice into my brain today. Over and over I keep listening to "I am I, old Father Fisheye that begat the ocean" and so on for four or so lines, then I skip ahead to the finale of the same poem—"The End"—over and over, "come Poet shut up eat my word, and taste my mouth in your ear." I can't get rid of it—the rhythm of the language, the performance of the poem, the hiply odd imagery.

Allen Ginsberg's voice into my brain today. Over and over I keep listening to "I am I, old Father Fisheye that begat the ocean" and so on for four or so lines, then I skip ahead to the finale of the same poem—"The End"—over and over, "come Poet shut up eat my word, and taste my mouth in your ear." I can't get rid of it—the rhythm of the language, the performance of the poem, the hiply odd imagery.So I'm breaking form. Instead of quixplicating a contemporary poem by a likely still living poet, I'm jotting down some thoughts on "The End." And, because I can't find a reliable version of the poem on the net, I'm including it here (I don't normally reprint) as it appears in my copy of Ginsberg's Selected Poems 1947-1995, originally from Kaddish and Other Poems (1961). Somewhere along the line I also acquired an audio version of it (probably from the aforementioned Mark Campbell). Listen from another tab as you read "The End" (Allen Ginsberg):

The End

I am I, old Father Fisheye that begat the ocean, the worm at my own ear, the serpent turning around a tree,

I sit in the mind of the oak and hide in the rose, I know if any wake up, none but my death,

come to me bodies, come to me prophecies, come all foreboding, come spirits and visions,

I receive all, I’ll die of cancer, I enter the coffin, forever, I close my eye, I disappear,

I fall on myself in winter snow, I roll in a great wheel through rain, I watch fuckers in convulsion,

car screech, furies groaning their basso music, memory fading in the brain, men imitating dogs,

I delight in a woman’s belly, youth stretching his breasts and thighs to sex, the cock sprung inward,

gassing its seed on the lips of Yin, the beasts dance in Siam, they sing opera in Moscow,

my boys yearn at dusk on stoops, I enter New York, I play my jazz on a Chicago Harpsichord,

Love that bore me I bear back to my Origin with no loss, I gloat over the vomiter

thrilled with my deathlessness, thrilled with this endlessness I dice and bury,

come Poet shut up eat my word, and taste my mouth in your ear.

One of the things I enjoy about "The End" is what I enjoy about a lot of Ginsberg's poetry: his performance of it. Too often I've been to a reading in which the fabulous on-the-page poet has bored me and much of the rest of the audience to yawns if not tears. Such a shame! One way or another, poems should be sung, and Ginsberg sung his well. The timbre of his voice unattractive but unique, and he reads with emotion and energy, two necessary traits too often lacking at a poetry reading—slam aside. Nothing better than a poet who knows how to read a poem—nothing worse than poets who read as though the audience isn't even present. For whom are they there?

I think, too, "The End" is a fair example of Ginsberg's aesthetics in general: the litany, the all-encompassing, the self-indulgent, the sexual, the visceral, the surreal, the Biblical cadences he co-opted from Whitman (among the other things he co-opted from Whitman and many others), the quasi-sloppiness. It's all there. Among my favorite moments is the poem's opening line, "I am I, old Father Fisheye that begat the ocean, the worm at my own ear, the serpent turning around a tree" and, of course, the closing line, "come poet shut up eat my word, and taste my mouth in your ear." Not only is the language raw and punchy and the rhythm riff-like with its spondee repetitions, but the image of the "ear" helps the poem arrive full circle. Notice how it's "my own ear" in line 1 but "your ear" in the last line. The poem's a Möbius strip.

I don't often think of Ginsberg's poetry as persona poetry, but I've always thought the "I" in "The End," the poem's speaker, wasn't Ginsberg. Who is "old Father Fisheye"? God? Death? Truly—it's Allan? I read the "Father" as some sort of Universal Mind figure, perhaps a reference to the Buddhist concept of Anatman, perhaps an amalgam of all the above. I don't believe it matters too much that we know exactly who the "Father" is, only that we know his vision is wide—like a fisheye lens. In this regard, the speaker is Allan Ginsberg, but only by default of the Anatman-like quality of the "I" in the poem. Ginsberg is one of the speaker's many selves. As he says, "I receive all." I've heard others discuss the speaker as Death, the end with a capital E, but there are too many beginnings in the poem for such a reading. "I delight in a woman's belly" makes me think of a pregnant woman, for example, the words "delight" and "belly" bearing several meaning's here. More likely the poem utilizes the cycle of life and death, the process of each occurring simultaneously such that one is not separate from the other but the other in a different form. Not sure if that makes sense, exactly... but the cycle, the simultaneity, runs throughout the poem as a central theme.

As such, I find the poem ironic. It isn't really "The End" at all, nor is it the beginning. And, assuming the speaker is not Allen Ginsberg but Allen Ginsberg assuming the voice of Father Fisheye, the poem is a call to the poet to shut up and listen for once. Ginsberg, as passionate as he was erudite, was no stranger to verbosity, yet here his speaker is telling him—the great "Poet"—to be quiet for a second, to meditate. This is appropriate given that "The End" is the last poem in Kaddish and Other Poems, a 100-or-so page collection titled after Ginsberg's "Kaddish," concerning the life and death of his mother. The story goes that Kaddish—a Jewish prayer given for the dead—wasn't recited at Ginsberg's mother's funeral. He wrestles with this fact for like two years, finally discusses it with friends, visits his mom's grave for the belated prayer, and shortly thereafter out comes the poem—something like that. So, 100 pages later, enough already. Perhaps that's a general call for enough already (although Ginsberg would go on to write a great free-for-all of poetry).

Ginsberg was one of the first poets I really fell in love with. I think I fell in love with all the first poets I read, actually, but my buddy Mark Campbell was something of a scholar of the Beats, and likely with his instigation Ginsberg has remained a favorite a mine while many of the others have come and gone. Strangely, as fresh as I find his language and style, I can't help but feel it's equally dated. Not so long ago I wrote about the "self" in poetry, prompted by the thoughts of poet Cam Scott (among other poets—the issue of the self in poetry not a twenty-first century dilemma). The common consensus is that too much me is a bad thing for poetry, a shunned thing even, but cripes—there's a lot of self-indulgent "I" in "The End," regardless of who it is or isn't. And that emphatic tone? It happens, but more often contemporary poetry's tone tends to the distant, the stoic, the monotone, the ... unemotional, though the content of the piece may be rather moving. We seem to have a distrust of language at that emotional level, the lingering effects, perhaps, of Language Poetry, more directly of disassociation and the intentional breaking of meaning and feeling.

Ginsberg never had problems with either one of those. In fact, often his poems come at you like a train, like the squeal of a sax, like he sung them via the technique of circular breathing. Always a success? No. But often worth listening to.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Janice Harrington's "The Divider"

The scene is this: we're in a nursing home, and it appears as though a person--an elderly person or someone resigned at an early age to such a place--has just died. We're bedside, removing "the cuff. . . .the gauze and alcohol. / . . . the stethoscope" and so on, item after item taken away, or cleaned and taken away, from the room. By the poem's end, we're still doing this, told to "Strip the mattress pad / and sheets. Sterilize the bed frame's metal / skeleton" and finally to "draw the divider, leave." The 16 line poem is rich with images, close-up details really, and although the language flirts with medical jargon, it remains common for the most part. The only oddball is "emesis" in line 6, and a quick search in my Oxford American Dictionary tells me that's the action or process of vomiting. Clear enough.

Most of these details are nursing home and caretaker related. They are rather impersonal (especially words like "emesis"), which is noteworthy since we're talking about a human being (and we're presumably being spoken to by a human being). Yet, few of the images bear a sense of the human. They don't personalize the poem's speaker nor its human subject. Only "the Christmas card" does this and briefly, hinting at human contact, yes, but also illustrating the lack of it. Where are the family photos? The other cards for birthdays and such, the items that would give to this person a sense of belonging, if not more specifically of family and friendship? Harrington goes on to write, "Later, take the personal belongings away or / give them to someone." But where are these personal items? Their absence in the poem, coupled with the litany of sterile image-laden commands, effectively removes the personal from the piece.

Harrington's use of an anonymous third-person speaker further illustrates this removal. Every sentence is an atonal command. Most are short: "Undo the cuff. Remove the gauze and alcohol." Those that do stretch across lines are lengthened only by more commands or by more images. There's nothing extra. No commentary. No existential blathering. No simile. No metaphor. Just a list of to-do items, as though the poem is being read from a manual--like one for how to put furniture together or, in this case, take it apart. There are no people in the poem, either. We have the speaker, and we have the deceased, but neither of them are mentioned. There are no names, and there are no personal pronouns. The personal, human element is gone.

This absence is superficial, of course. In fact, there's a great deal of humanity in the poem, and in some ways the poem's overt lack of it only draws a greater attention to what lies beneath, that we are dealing with people here, not just a body, not just a nurse or caretaker who turns impersonal in order to get the job done—removing the deceased, preparing the room for the next person for whom death is but a matter of time. So, the distance in the poem--this division between between feeling and unfeeling--comes into question, then. Does such a stance illustrate the speaker's habitual use of necessary distance? Is it strictly a defense mechanism? Is it simply part of the job? Or does it speak more specifically to human nature and one of the ways we instinctively deal with death?

To this end, Harrington closes the poem with "Do all this—but for now just close / its scrim around the bed, draw the divider, leave." But why must we leave? Are we—is the speaker—emotionally overwhelmed or risking it and, therefore, risking the ability to effectively get the ensuing job done? Is it because we're too busy with other jobs in the home to pay attention to the deceased even now? Is this—is the whole poem—an issue of neglect?

For such a seemingly easy poem, I appreciate the fact "The Divider" leaves me hanging. If the poem closed down, instead of opening up, I fear it would be less successful. Ending with ambivalence, however, offers the poem possibilities and reason for discussion—one of the reasons I think the piece apropos for a beginning poetry class. "The Divider" is not intimidating in any way, yet it's not as easy to grasp as it first appears. There's more to it, a multiplicity that is necessary for its success—arguably for any poem's success. The title itself—"The Divider"—illustrates this multiplicity. The divider can be the literal curtain referred to in the last line of the poem. It can be death. It can be the wall the speaker uses to separate herself from the situation. It can be any of these simultaneously, which is the poem's true power. In the physical world (although quantum physics may disagree with this . . . ), something cannot exist in two or more places at once. In artful poetry, this is the norm: an image, a word, a phrase, a line existing in multiple, valid layers of meaning simultaneously.

I have a good deal to say about Harrington's acoustic texture in "The Divider" as well. It's a percussive poem with what feels like a conscious attention to the noise it makes, another reason I think it useful to beginning poets. It is not musical per se, nor rhythmic, but nearly every line evokes a solid sense of sound via alliteration, consonance in particular, as well as via Harrington's repetitive use of short, imperative clauses. I can't help but wonder if Harrington's awareness of language is what helped her arrive at words like "emesis" and "Kleenex" a few lines later—said awareness being what drove the arrival of the language here more than the poem's topical matter did. I'm conjecturing, of course.

And I'll leave others—perhaps in that intro course—to find further examples of assonance and consonance, slant rhyme and so on.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Damon McLaughlin @ Best American Poetry--Vital Signs

For my last trick this week, I’m going to write about some ideas I had when at Toad Hall. I think we were talking about Flarf and Language poetry when one of us—or maybe I thought of this after the fact . . . I can’t remember—voiced a unique theory on their origins: so many resources and years and years of traditions and movements had become available to us poets, we suddenly had to dump the excess. That is to say—we had to use the excess, even if it was garbage, because it was there and we could. These movements, then, arose less as rebellion than as corollary. They weren’t commentaries but consequences.

For my last trick this week, I’m going to write about some ideas I had when at Toad Hall. I think we were talking about Flarf and Language poetry when one of us—or maybe I thought of this after the fact . . . I can’t remember—voiced a unique theory on their origins: so many resources and years and years of traditions and movements had become available to us poets, we suddenly had to dump the excess. That is to say—we had to use the excess, even if it was garbage, because it was there and we could. These movements, then, arose less as rebellion than as corollary. They weren’t commentaries but consequences.While I appreciate the original Language poets for their innovation and application of theory and politics to political practice, I don’t often love their poems. I enjoy the experiment—and have learned from it—but I find much of the emotion in that poetry stilted, and that’s just not my personal preference. Whether the poems are accessible, so to speak, is inconsequential. Generally I can’t (and shouldn’t) approach an Armantrout piece with the same lens I use for a Collins poem, so I’m not bothered when I don’t get it—anyway that’s rarely the point of any poem. As for Flarf, I think—so what? When things are new, they’re exciting and sharp. Over time, much sloppiness ensues.

At the same time I can’t help but think how wonderful it is we live during these (according to theory) excessive, extravagant years in which movements like Flarf can germinate and be popularized, in which we can grant time for these art forms, to not tax the rich, to have lockouts over the salaries of professional athletes, to afford personal computers in all shapes and sizes and—nearly—in all things, to market almost any extravagantly unnecessary item and, in an ironic twist, deem it a must-have even in these dire times because well—why not? If we want, we need. If we can, we must. It’s a basic, underlying proposition of the United States of America.

Read the rest @ Best American Poetry -- my last post as Guest Blogger.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Damon McLaughlin @ Best New Poetry--Runnin' Down a Dream

. . . is it possible such habits—such things as routine exercise, diet, routine sleep patterns, and so on—can affect not only our ability to imagine but also our ability to write? They must, but—I mean—what if there’s a recipe for good poetry, and it includes things like—50 sit-ups and push-ups daily, preferably before breakfast, which should be comprised of 1 mango and a cup of Greek yogurt, preferably with a drop of honey, and one 8 oz. cup of medium roast coffee, preferably a single-origin bean from Latin America, all of which should be consumed within 12-15 minutes for optimal imaginative prowess, and so on, and so on throughout the day, each ingredient and the ingredients in tandem resulting in a specific mental effect. What if—worse—that recipe is like a baking recipe, which can’t really be fiddled with or you’ll the ruin the cheesecake, the custard, what-have-you. I know there’s a growing science on creativity and on how genes and the environment interact and on how such interaction affects the brain. What if these researchers discover a formula for the muse? The diet-exercise plan for sonnets? The Shakespeare diet? The Billy Collins Diet? The Ashbery Plan? What if the success of your craft was as dependent on the other mental processes as it was on those related to poetry?

. . . is it possible such habits—such things as routine exercise, diet, routine sleep patterns, and so on—can affect not only our ability to imagine but also our ability to write? They must, but—I mean—what if there’s a recipe for good poetry, and it includes things like—50 sit-ups and push-ups daily, preferably before breakfast, which should be comprised of 1 mango and a cup of Greek yogurt, preferably with a drop of honey, and one 8 oz. cup of medium roast coffee, preferably a single-origin bean from Latin America, all of which should be consumed within 12-15 minutes for optimal imaginative prowess, and so on, and so on throughout the day, each ingredient and the ingredients in tandem resulting in a specific mental effect. What if—worse—that recipe is like a baking recipe, which can’t really be fiddled with or you’ll the ruin the cheesecake, the custard, what-have-you. I know there’s a growing science on creativity and on how genes and the environment interact and on how such interaction affects the brain. What if these researchers discover a formula for the muse? The diet-exercise plan for sonnets? The Shakespeare diet? The Billy Collins Diet? The Ashbery Plan? What if the success of your craft was as dependent on the other mental processes as it was on those related to poetry?Read the rest @ Best American Poetry.

Tuesday, September 20, 2011

Damon McLaughlin @ Best American Poetry--Form for Thought

In his initial discussion of tone languages in Music, Language, and the Brain, Aniriddh D. Patel writes briefly of the Chinantec, an indigenous people of southern Mexico, who utilize a whistled speech in addition to their tonal, spoken word. They use whistle combinations “of tone and stress distinctions to communicate messages with minimal ambiguity.” And he’s not talking about a hey! or an over here! or some ridiculous catcall. He’s suggesting they actually have a whistle language. . .

In his initial discussion of tone languages in Music, Language, and the Brain, Aniriddh D. Patel writes briefly of the Chinantec, an indigenous people of southern Mexico, who utilize a whistled speech in addition to their tonal, spoken word. They use whistle combinations “of tone and stress distinctions to communicate messages with minimal ambiguity.” And he’s not talking about a hey! or an over here! or some ridiculous catcall. He’s suggesting they actually have a whistle language. . .Read the rest @ Best American Poetry.

Monday, September 19, 2011

Damon McLaughlin @ Best American Poetry-- Cameron Scott asks...

A few days ago, poet Cameron Scott sent out an email that asked “What role should ‘the self’ play in a poem? In other words should a poem be about the self as little as possible, or what the heck, it’s all about me?” He’s a contributing editor for CheekTeeth, the blog for Trachodon Magazine, and is looking to incorporates responses into a future post. With his permission, I asked that I respond here at Best American Poetry.

A few days ago, poet Cameron Scott sent out an email that asked “What role should ‘the self’ play in a poem? In other words should a poem be about the self as little as possible, or what the heck, it’s all about me?” He’s a contributing editor for CheekTeeth, the blog for Trachodon Magazine, and is looking to incorporates responses into a future post. With his permission, I asked that I respond here at Best American Poetry.Read the rest @ Best American Poetry.

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Damon McLaughlin @ Best American Poetry--Oysters, Pure and Simple

When my mother and I were recently, briefly in Boston, she wouldn’t try oysters. We’d been in New Hampshire at Toad Hall (see previous post), and that day Legal Harborside was our final destination before we headed out. We had just enough time for lunch before returning our rental car and catching our planes. . .

When my mother and I were recently, briefly in Boston, she wouldn’t try oysters. We’d been in New Hampshire at Toad Hall (see previous post), and that day Legal Harborside was our final destination before we headed out. We had just enough time for lunch before returning our rental car and catching our planes. . .Read the rest at Best American Poetry.

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Damon McLaughlin @ Best American Poetry--Thank You, Brenda Hillman

Read more @ the Best American Poetry blog, where I am the guest blogger this week. Look forward to posts about the "self," oysters, the mind-body connection, and Emily Dickinson -- that's the plan anyway. On any given morning, who knows what will happen?

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Bicycle Riding, Teaching Poetry, and David Ignatow's "The Bagel"

And I thought there must be a poem I can post about this joy of bicycling. What came to mind instead was David Ignatow's "The Bagel,"perhaps the most joyful poem of all time.

And I intended to share it here and not say too much else about it. Problem is--one of the first links I tabbed in Safari turned out to be a brief analysis of Ignatow's poem at Elite Skills, a "Poetry and Writing Workshop" website. What I read so irked me--I no longer found myself capable of just dropping a link. I don't believe the text is copyright sensitive, so here it is:

Recently in our English class, we deciphered David Ignatow's The Bagel. We discovered deeper meaning and found that the bagel was a metaphor for the man's childhood. At first the man thinks childhood is something he wants to give away and get rid of but then realizes that he needs it. When chasing the "bagel" down the street he turns into a "bagel" himself, meaning while chasing down his childhood he relives some of the fun of his childhood that he initially wanted to give away.

While the analysis is not exactly off, it reeks of a high school English class (egad! this could be a college course...) whose coaching on the matter does little service to poetry and its pleasures at large. In fact, it does a grave disservice. Of course, I am making some assumptions here, which is a bit unfair, but--I doubt the writer of this little blob came up with the explanation on his own.

More likely, based on my experience as a former poetry-hating high school student and my conversations with many other former and current poetry-hating high school students, the writer was told, with a bit of pseudo-prompting common to the poor teaching of poetry, what the poem was about. Words like "deciphered" and "deeper meaning" lead me to this conclusion, as does the notion that "the bagel was a metaphor for the man's childhood." I mean--really? The bagel equals childhood? So then, in the poem's penultimate line, we can insert "childhood" for "bagel" such that the speaker rolls "one complete somersault / after another like a childhood / and strangely happy with [him]self"? I don't think so, Bub. That would elevate the bagel to the level of symbol, and the symbol is dead. Why must teachers of English (they hardly teach poetry . . . or English for that matter) revert to the symbol? Why must this always stand for that? I avoided what I thought was poetry for a long time due to such a pedagogical stance and ingraining. As for Ignatow, "The Bagel," and Elite Skills, the bagel does not stand for childhood in any way, shape, or form.

However, this moment, this wonderful, magical moment when the speaker turns into the bagel, somersault by somersault, is certainly child-like, so I can see where such a leap could be erroneously made. But it's this moment that evokes childhood, not the bagel. It's the pleasure of turning lemons into lemonade by surprise--an unforeseen joy--that takes the speaker, the poem, and its readers into the fun of being a kid. Who else could turn into a bagel and roll down the street? Certainly not the old man who wrote the poem (Ignatow was born in 1914). So, yes. There is some truth to that analysis when it says the speaker does relive "some of the fun of his childhood," but in no way is he chasing it down. In no way does he want "to give [it] away . . . then realizes that he needs it." Nothing in the poem leads readers to such "deeper meaning" conclusions. In fact, those ideas are just wrong. I mean--the speaker says directly he was "annoyed with [him]self / for having dropped it." He didn't give anything away.

So, yes, deeper meaning. It seems to me that poems that work offer everything--or just about everything--a reader needs right on the surface. It's all right there in direct view, open sunlight. The problem is that we are trained in our early years to believe that poetry is a code, that it is a mystery that must be figured out, that its words are clues to some vast, hidden agenda that lies deep below the surface of the poem, and so we learn to look past the surface into some abyss where answers apparently lie. I am not arguing that good poems don't work in layers. They do. I'm simply saying "the answer" isn't there. There is no answer. There is no code to break--generally speaking--and there is no hidden mystery. If there was, then what's all that stuff at the surface if not a cover-up? The poetry becomes a mechanism for hiding meaning and truth--the true meaning of a poem--instead of a mechanism for revealing such matters. To say there is a hidden meaning--a deeper meaning, whatever--altogether negates the purpose of writing poems, which is to express and reveal, not to hide and conceal. There are always exceptions to the norm, of course, but Ignatow's "The Bagel" is not one of them.

Really, my beef with all this is that when teachers teach poems in this manner of deciphering and such, they really mistreat the art of poetry. They relegate it to the role of legerdemain and bypass all the quality craft-stuff that makes a worthwhile poem worthwhile. An additional detriment, by treating a poem like a Rubik's cube, teachers tell students that once it's been figured out, it's done. It's over. It's--solved. And then students don't see the poem as an experience; they see it as a trick to be mastered, a question to be answered, when in fact that's hardly ever the case. Consider it's the journey, as "The Bagel" suggests, not the goal.

Anyway, I think my daughter has had a few bagel-like experiences these past few days, and I with her. Pure, unadulterated joy. And there's no mystery in that.

Friday, September 9, 2011

Rain Song #1, circa 1999, the JimRobbie Trio

Jake, Andrew, and I recorded the album in this guy's home studio on an 8 track recorder that served it's purposes well at the time. I can still remember the setup, where Andrew's kit was positioned, the green curtain that separated Seth, our producer of sorts, from the rest of the band. More than anything I recall how cold it was, like hurt-your-teeth cold, then stepping out into it anyway for a cigarette between sessions.

Jake, Andrew, and I recorded the album in this guy's home studio on an 8 track recorder that served it's purposes well at the time. I can still remember the setup, where Andrew's kit was positioned, the green curtain that separated Seth, our producer of sorts, from the rest of the band. More than anything I recall how cold it was, like hurt-your-teeth cold, then stepping out into it anyway for a cigarette between sessions.Listening to the song now I think how Andrew is to splash cymbal what Will Ferrell is to cowbell. And I wish I could get rid of that little buzz on my guitar. Jake, as always, sounds great. And did I mention it was through Jake that we conned George Dalton--a radio journalist from our local NPR affiliate--to open the song with a little intro? Can't beat it, just can't beat it.

As for other comments about the recording and the band, we were working sort of from a minimalist viewpoint, which meant as little extra as possible: no over-effecting, definitely no over-producing. I'm still sort of into that, musically speaking.

So, please, enjoy "Rain Song #1." Feel free to hear a me-and-my-acoustic version--complete with its mistakes--on my Music page.

Saturday, September 3, 2011

New RSR video added from last weekend's Plush show

Our anti-finale finale at Plush last Saturday 8-27-11, "Swiss Valley Road," recorded by Cheryl on the fan-cam: RSR - Swiss Valley Road.

Our anti-finale finale at Plush last Saturday 8-27-11, "Swiss Valley Road," recorded by Cheryl on the fan-cam: RSR - Swiss Valley Road.Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Mahmoud Darwish's "Your Night is of Lilac"

At first I thought I heard a preponderance of dactyls in the poem's falling rhythms, but after a second reading, I don't think that's the case anymore. The poem is musical, yes, but it doesn't utilize meter--even in pieces--toward that end as much as it does smaller units of sound, namely its vowels and a few select consonants. The line that best exhibits what I'm talking about can be found 6 lines up from the bottom:

endlessness, nothing celebrates it except its mirror

Here I hear a whole lot of "S" and a bit of "R," the most-loved consonants in the poem, and I think I know why: they have great sustain. That is to say, they require time to be pronounced, "S" because it lingers on the tongue as a sibilant, and "R" because it is voiced first (as opposed to voiceless), and breathy second. As soft consonants, each requires breath as it expires, as in endlessness and mirror. You can't stop those words--those sounds--short. Even after the vocal cords have have quit, they continue as a whisper (hmmm...whiSpeR...).

In the poem, "S" and "R" can be found everywhere, thus slowing the poem's pace and effectively granting it a serenity (hmmm...there they are again. coincidence?) apropos of the poem's content--it's something of a tranquil, romantic piece about poetry, possibly a lover. In the above quoted line, that slow, steadiness is easy to hear. In that case, too, the lack of monosyllabic words helps steady the pace and tone: "endlessness, nothing celebrates it except its mirror". And, the line is long. Although line length in and of itself is not necessarily the cause of rhythmic poetry, a longish line does have a tendency to allow rhythms to build in a way that a shorter line--simply due to its length--cannot. Consider this hacking of the Darwish line:

endlessness, nothing

celebrates it

except its mirror

Its continuity is broken now, not only into three lines, but into relative arrhythmia. The consonants, especially the "S," no longer have their sense of contiguity, thus the music falters.

As for the vowels, Darwish-through-Joudah likes them long, especially his "I." This is for the same reason he likes his "S" and "R": a long vowel is drawn out over time, and a short vowel is clipped. Thus, an abundance of long "I" and "E" and so on is likely to slow the poem's pace and help its tone settle into a calm.

If you're not buying this business about the sounds of vowels and consonants, consider a few words we use for bodies of water. I'll list them in the order from small, insignificant bodies to large, demanding ones. Note the use of hard and soft consonants as well as the use of long and short vowels. Picture in your mind the image as you listen to the sound of each word: crick, creek, pond, river, lake, sea, ocean. Maybe I'm being far-fetched, but the sound of each water word seems indicative of the size and presence of the body it represents. A crick is something that runs through the woods near your backyard. Maybe it contains some small fish. It certainly begins and ends with a hard consonant and shoves a short, stubby vowel in the middle. A sea is vast, virtually endless to the eye, though the brain is wiser (and deeper...). Like the word that represents it, it just sort of disappears silently off the horizon. It hits the shore with an "S" and ebbs back to the edge of the Earth with an "E."

Anyway, the first line of "Your Night is of Lilac" demonstrates what I'm talking about with regard to the poem's sounds:

The night sits wherever you are. Your night

"S" and "R" are there of course. Then we have the long "I" repeated in the word "night," the long "O" in "Your." Particularly, it's that pair of long vowels and the consonance of "R" at the end of the line that really extends the line's music. The beginning of the next line, too, is constructed in sharp contrast to this extension, highlighting those opening sounds in effect: ". . . is of lilac" is read quickly, running over its lone long "I" with the preceding short one and the hard "C" with which it ends. Interestingly, the poem slows and becomes rhythmic again for another line and a half or so, only to be clipped at "and lights up" in line 4, a nice echo of "lilac" in line two in terms of sound and placement.

I could go on, but I don't care to parse "Your Night is Lilac" any further. And that's pretty much the hard and soft, the long and short of it. As for content, I think that line about endlessness pretty well says enough. I also like "Night / is the covenant of night." This is a love poem after all, and well, what else is there to say?

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Burn, Baby, Burn: On Shivani's thoughts of Graham, Olds, Levine, and Gluck

Truth be told—I enjoyed the reading. Graham’s words spoke to me on a different level than they did on the page. I suppose I was more easily caught up in the airy, ephemeralness of her speech than I was of her written language, which for me was then largely as it is now: intriguing, intelligent, layered, occasionally an imbroglio, not terribly pleasurable but enjoyable for its leaps in thought as well structure, for its difficulty. I'm not a lover of her work, but I was honestly taken by her reading of it. And, I would contend that despite my lack of pleasure with her poems in writing, not to be confused with a lack of appreciation, she is absolutely worth reading because of her style, influence, success, and longevity—not necessarily in that order.

I would say the same for Sharon Olds, Louise Glück, and Phil Levine—three poets I’ve enjoyed immensely. So, naturally, I felt annoyed when I read Anis Shivani’s recent article in the Huffington Post: “Philip Levine and Other Mediocrities: What it takes to ascend to the Poet Laureateship.” He claims these poets—including Graham—have let their poetries fall into severe tedium and disrepair with which, mind you, they have waddled among the muck of unwarranted success for decades, their prizes and reputations riding largely on poetry-guild nepotism, which Shivani discusses a bit in “Beautiful and Pointless: New York Times Poetry Critic Says Poetry Isn’t Relevant,” an earlier post of his in the Huffington.

Actually, a fair amount of his observations, stripped of their pejorative décor, are accurate. I agree with him that Olds writes of the body and birth, Graham of material in a thought-world, Glück of the personal and its various sensitive hats, and Levine of the humdrum working life he may or may not have lived. But that’s all subject matter, and I don’t see how someone can be against subject matter. Lack of craft, lack of tempered skill—yes. But content? I mean—so what if these poets choose to write about these things? When I’m dead and famous—preferably not in that order—people may complain that my poems are obsessed with fish and birds, but I hope they don’t consider them trash as a result. This is America, dammit. Isn’t everything fair game?

Ted Kooser, an ex-Laureate himself, has a few nice things to say about content in an interview he did with Grace Cavalieri on her stellar radio show Poet and The Poem. He mentions that one of his ambitions was to be able to write a poem about anything, anything, and so he recounts the brief backstory of his “The Washing of Hands,” a completely mundane and—in the context of the poem—domestic task. The piece is terrific. But the content is banal. I mean—a poem about a woman washing her hands? Oh, yawn. But it’s what happens inside the poem as a reading experience that really kicks. That’s the poetry, not the theme or whatever.

My point is that content and its extensions just don’t really matter that much. They’re beside the point. And this is the truth for so many aspects of life—isn’t life not about what we fill our time with but how we fill it—why should poetry be any different? I got into a similar argument a long time ago with Kathleen Peirce over a Bukowski poem, “The Apple,” which I claimed was about meaninglessness and, therefore, was itself meaningless, and that that was the most beautiful thing about it—that what the poet (and for me, the reader) walked away with was that he walked away with nothing.

This is the self-defeating portion of my argument, of course. Poems must mean something after all. I’m just saying that’s not the point. Poems should not be judged by subject matter or theme but by their artistic risks and successes. The wrong question is always asked: What does it mean? That’s the scourge of poetry’s disfavor in high schools around the world—god forbid it ever be asked of children in the lower grades! The question should be—is it artful? If we asked that, maybe our kids would actually learn something about poetry other than that they don’t care for it. I contend they would learn a great deal, in fact, by wondering about the answer to that question.

Unfortunately, like so much talk about poetry and so many of its critics—both for and against—Shivani more or less avoids such an inquiry other than by blanket statement, degrading the work of some terrific poets—if not the poets themselves. As early as his essay’s second paragraph, Shivani writes of Graham, Olds, Glück and Levine, “Their very project is to participate. . .in the annihilation of common decency at all levels.” Seriously. I mean—seriously? We once burned witches over similar claims. I hope we don’t start burning poets.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

RSR tunes added...

Tunes, videos, and downloads have been added to the Present Everywhere Music/RSR page. All downloads are free to inclined listeners--both live and studio cuts. Same for my own acoustic tracks--no frills free downloads. Have a listen, leave a comment, read a poem here or elsewhere. "For what, ultimately, does poetry say to us? It says that if we shoot a bird, we wound ourselves."

Tunes, videos, and downloads have been added to the Present Everywhere Music/RSR page. All downloads are free to inclined listeners--both live and studio cuts. Same for my own acoustic tracks--no frills free downloads. Have a listen, leave a comment, read a poem here or elsewhere. "For what, ultimately, does poetry say to us? It says that if we shoot a bird, we wound ourselves."

Friday, August 12, 2011

Chris Abani's "In the Middle of Dinner"

And I think that works well for Abani's "In the Middle of Dinner" (I'll let others make their own decisions about my piece...). The poem's loose ends don't make it feel incomplete but mysterious, and there's plenty of info in the piece for readers to make an educated conjecture about what just happened. We don't need to know the whole story to know what's going on.

The narrative to the poem is this: the speaker and his mother are in the middle of dinner--prime rib--when she stops eating, moves her wedding band from ring to middle finger, says a few words regarding her absent husband (absent at least five years), then returns to matters at hand--the prime rib. The moment is over and done with in less time than it takes to chew a piece of meat. The mother's comment about her husband, which is set-up to be important, becomes nearly off-hand. Thus, the poem ends a bit confusingly: say what? What?

Structurally, though, Abani does a few things to help us keep hold of the poem, which is cool: we're grasping for meaning through how the poem is made, not (solely) by what it says. For starters, he uses dinner imagery to encapsulate the poem's moment spatially as well as temporally. He opens with the title, which acts as the first line--"In the Middle of Dinner"--then, "my mother put down her knife and fork." And, he ends with "This / prime rib is really tender, isn't it? she asked." These are the only lines that have anything to do with eating dinner, with the literal physical space of the narrative. Because they are bookends, they work well as signals into the poem and out, effectively containing the poem's true meat and potatoes within a nice, little box. Readers more or less finish where they started although a great deal has changed.

As well, though the action between that opening and ending line--literally in the middle of dinner--seems relatively quick, time in the poem slows down there. The action, wrapped up with the mother's revelation, becomes gradual, drawn-out. Those dinner-imagery bookends, however, keep the poem in place and ultimately at normal speed. They don't necessarily do this by increasing the pace but by acting as cues to readers that we are back from wherever we went with mother and son, with absent husband. It's as though we've stepped out of time and place and have returned. I like this because--to me--this is the experience of poetry at large. To write a poem is to definitely step outside time and place. I say this because I've lost track of both when engaged by the muse and know what it's like--as I'm certain many if not most poets do--to be someplace else even though I'm at the desk. My wife calls this being in my head. But, to be frank--I'm hardly there.

Reading a poem is not all that different. Often to enjoy a piece one has to enter the poem's time and place. That is part of the reading-poetry experience, and though it is not always required by a poem, I find most poems are better enjoyed when I can do this. They are microcosms with their own weather patterns. I won't experience their rain and snow and sunshine if I don't go there, so to speak. You won't either. In fact--I'd be willing to bet most people at large have no idea about this. Thus, they opt for pulp instead of poetry and have disdain for poems because they don't "understand" them.

But that's another blog probably, so--

What I was saying was--I like how Abani encapsulate's the poem with dinner imagery, the last line working as an echo of the first, thereby focusing reader attention in that moment that matters most. He uses repetition/echo in a few other places, too. In the very middle line--line 6 of 11--he writes of the mother, "Five years, she said, five years, once a week," explaining how often and for how long she wrote to her absent husband. This is echoed in the antepenultimate line with "Not one letter back, not a single note." I liken these lines to call and response although they are not so cut and dried as that. They help fill in the narrative---the backstory--and give readers the chance to think back in the poem. That's one of the effects of repetition is that it makes us think of what we've already read, of what's being repeated, in this case by the syntactic repetition of the lines--not their words or images per se.

The other repetition of note is the word tender, located in line 5 to describe the way the mother moves her wedding band from ring finger to middle finger--an interesting act in and of itself. Abani writes, "So natural was the move, / so tender, I almost didn't notice." In the last line he again uses tender. The mother says, "This / prime rib is really tender, isn't it?" Obviously tender is being used in two very different contexts here, but I can't help but sense the connection. Words are too precious to waste for most poets, so a repetition like this within such a small, short space has got to be for something. It could be repetition used to kick readers back into the poem, similar to how I discussed the earlier example, but I doubt it because that is the nature of repetition anyway. Abani wouldn't be getting much work out of the one word tender if that's the sole case here. I think he does it for two other reasons.

First, it helps demonstrate the mother's change, her epiphany or whatever she's had, through the ritual of moving the ring from finger to finger. There is something very tender about that moment, that exchange between mother and son, about the revelation of her feelings to him (and to herself), but there is nothing tender in that last line except the word itself. A simple comparison of rhythm and pace demonstrates this. You can't read "So natural was the move, / so tender, I almost didn't notice" glibly in the poem; and, you can't read "This / prime rib is really tender, isn't it?" with terrific ardor. It just ain't right that way. The effect is that the mother is now seen in a new light--and in fact she may be living in a new light, having passed through the loss of her husband, having more fully processed her grief--signified by that ring ritual--than she had done so before.

Second, and related to the above, that prime rib tender helps snap the poem out of the timeless space in the middle of dinner. We went on this brief sojourn with the mother, but--we're back, so to speak. That second use of tender does kick readers back up into the earlier language of the poem, but it doesn't kick us into that earlier portion's time and space. Instead, distance is created here. If the earlier repetition--that of the syntactic structure of those two lines--is used to tie together, this instance is used to separate.

Other aspects of Abani's piece? I like the image the mother uses to explain her lingering hope of her husband's return, that she "waited / until time was like ash on my tongue." It's a strange but effective image in that ash is the end of things--ashes to ashes, and so on--but, therefore, also the beginning. As a literal image, it would certainly provide a foul taste and texture, so it's apropos for the mother who seems to have waited and waited until she was sick of waiting, until it--perhaps finally--left a bad taste in her mouth. And, because the tongue is involved, it's an echo of eating. Consequently, it continues to pull the poem together and to allow other connections to be made between lines, between the poem's times and places that seem to be disparate and homogeneous simultaneously. Ash, too, may give readers a clue as to the husband's whereabouts. Perhaps he's passed on? Maybe he's just finally dead to me now, in the voice of the mother, but that seems far too trite a read.

Lastly, the poem sort of wears the guise of a sonnet. It's more or less a box of uniform lines--roughly 4 non-metrical beats per line for 11 lines--opens with an early end rhyme that made me think of a possible Shakespearean sonnet twist, and it is a love poem of sorts. Although I would not call "In the Middle of Dinner" a sonnet, I think considering the piece in the light of one does provide a worthwhile entry into it. This is a poem where the facts are open to possibility, and I think that's the case not just in terms of the narrative but in the poetry used to tell it.

Sunday, August 7, 2011

Olduvai Theory now for sale

[/caption]

[/caption]Limited edition, hand-bound copies of my chapbook Olduvai Theory, which won the 2011 Toad Hall Press Chapbook Prize, are now available on the BOOKS page of my website. My first collection Exchanging Lives is also available.

On the MUSIC page, all tunes are now available for free download. Songs from the Red Star Rebellion catalog will be added within the coming days.

And, hopefully, I'll have another quixplication online this week, too... been playing catch-up in all departments these days.

Sunday, July 31, 2011

"Watching Fog Roll Off The Shack At Toad Hall Pond"

This white-picket life once was dangerous:

snow caves in winter, quicksand in summer.

Nothing in this world was sacred.

I ran away through backwoods, through nettles

and poison oak, scrabbled over barbed wire.

This American life once was dangerous;

it took my every immunity to rush the Brahman

in the field. Now I walk as though on clover.

Nothing in this world can be sacred.

Each of my children is a dandelion clock.

I foreknow their sail over this river in the sky.

This white-picket life once was dangerous

before such letting go, such letting slip

the cordage that bound me to any of my beloved.

Nothing in this world could be sacred,

not spring, not fall, the rouge of any Roman dusk.

This white-picket life once was dangerous

although it was a gross, disintegrating menagerie.

Nothing in this life is sacred.

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Sunday, July 24, 2011

This Writing Life... an excellent new post at the Cheek Teeth blog

has posted yet another stellar essay at Cheek Teeth -- about the joys and displeasures of living as a writer in these times. It's a read lush with images and craftsmanship--readers of pulp/pop fiction beware!

has posted yet another stellar essay at Cheek Teeth -- about the joys and displeasures of living as a writer in these times. It's a read lush with images and craftsmanship--readers of pulp/pop fiction beware!"What It Takes to Make a (Writing) Life"

Saturday, July 23, 2011

Invitation...

Toad Hall

2330 Benton Road N. Haverhill NH 03774

Tel 603.787.9823

toadhallmedia.com

The editors and publisher of Toad Hall Press hope you will please join us Sunday July 31, 2011, 2–4 PM, to celebrate the publication of Damon McLaughlin’s chapbook, Olduvai Theory, winner of the 2011 Toad Hall Chapbook Contest. The party will be at Toad Hall, at the address shown above.

The author is flying in from Tucson for the launch of the book, and poets and writers from across the US will also attend.

Toad Hall is proud to serve wine from the Vineyard at Seven Birches, our neighbor, and the creations of chef Dina Dubey of No Thyme to Cook. We promise great poetry, food, and wine.

Please let me know if you can come! E-mail mariac@indexing.com or telephone 603 787-9823.

Advance praise for Olduvai Theory:

From the dawn of history to the end of time, Damon McLaughlin’s ecstatic jeremiads and coruscating haiku-like lyrics trace the trajectory of civilization across cosmic Big Bang, Pangean pea soup, eons-long bebop to the extravagant hopes and daily despair of our own American good-night. “I don’t know if this is/our first sun dance or our last,” the poet warns, “but the drums are coming./They’re coming, and a new mutilation will begin.” These are urgent poems for our darkly emergent times.

-L. S. Asekoff

In the face of predictions that earthly catastrophe is on its way, Olduvai Theory serves up poems that tear through the language like strife, as though freeing propriety from bondage: “I don’t know if this is // our first sun dance or our last, but the drums are coming. / They’re coming, and a new mutilation will begin.” They can also sidle up to you with the delicacy of the ephemeral: “Lights of the city / float / one thousand paper lanterns.” Often raucous and outrageous in tone – at times surreal and ecstatic, if not dark with foreboding, Damon McLaughlin’s poems possess an assured and commanding voice.

-Merrill Leffler

Damon McLaughlin's chapbook Olduvai Theory predicts "this great something's end" then asks "Why give it a name?" Like Matthew Arnold, McLaughlin knows that love is the only answer in the face of the unanswerable, "Come here my darling, my moonbeam, my honeybunch. / These are questions to which you are the only answer..." This powerful collection explores the beginnings and endings we face every day and culminates with the epic "A Day in the Life of America." You won't be disappointed.

-Shaindel Beers

Maria van Beuren

Editor-in-Chief, Toad Hall Press

Thursday, July 7, 2011

e.e. cummings' [love is more thicker than forget]

The poem is composed of 4 quatrains written in an ABAB common verse, a ballad form used by many poets of the past (and of the present and future?) including Dickinson (who used a true ballad stanza of ABCB and to whom I will return to later). This easy, consistent meter and rhyme scheme gives the poem a sing-song like quality, which adds to its fun--at least to this contemporary ear--and keeps the stanzas in neat little digestible packages. cummings also employs a significant amount of alliteration, sometimes stretching the device across two lines, as he does with the "TH" sound in the poem's opening--"love is more thicker than forget/ more thinner than recall"--and sometimes squeezing it into a single line as he does here with "M"--"love is more mad and moonly." In brief, soundPLAY is throughout.

But for all the play, there's some meat to the poem, too. For all those comparisons--love is more than, love is less than, etc.--cummings' descriptions of love are unique and not at all inaccurate. We all feel it, but who can describe it precisely? It's an irrational, gut feeling that cannot be precisely compartmentalized and explained; nevertheless, we all know it when we feel it--lust/love confusions aside. Burn's "O my Luve's like a red, red rose" is nice but quaint. I think I prefer the euphoric silliness of cummings' descriptions.

I prefer two of his descriptions most of all, and they are contained in the second and fourth stanzas respectively:

it is more mad and moonly

and less it shall unbe

than all the sea which only

is deeper than the sea

it is most sane and sunly

and more it cannot die

than all the sky which only

is higher than the sky

A few cool things happen here. Although every stanza is an echo of every other because of the demands of the form, these two are more exact, which gives the last stanza punch and the poem closure. "Moonly" (female) and "sunly" (male) are a nice pair, given the poem's theme, and of course the repetition of "only" helps bind the stanzas together. It's interesting, too, each of those instances state how one thing and only one thing is more or less than itself: only the sea is deeper than the sea, and only the sky is higher than the sky. Is there a better metaphor for describing love at its largest ineffability?

But what I most enjoy about this poem is its reference in these stanzas to Emily Dickinson's "The Brain—is wider than the sky—". In this piece, Dickinson writes about the powers of the imagination, using both sky and sea in the way--more or less--that cummings does to describe love. Substitute love for the brain in the Dickinson poem, and it still makes perfect sense (although the brain is much more Dickinson...). As to the power of either, both poets more or less have the same to say, illustrating how closely linked these two pieces are, though they were written maybe...80 years apart.

So, for all his unique cleverness, cummings' is a pilferer. Who was it who said "mediocre writers borrow, great writers steal"? Eliot? Yet again that adage rings true.

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Lisa Williams' "Wing"

But I didn't choose to write about "Wing" because of its content. I chose to write about it because of a recent blip of a blog written by Cameron Scott at Cheekteeth, the blog for Trachodon Magazine. In his "Line Breaks and Broken Transmissions," Scott writes that "for the most part line breaks are arbitrary; if you are writing a poem you have to do it, and you don't have to think about it most of the time." This follows a sentence that briefly describes how lines and line breaks can be determined by breathing, which does comes naturally and does not require thought, but nevertheless—as a poet who cares a great deal more about his line breaks than his content, I couldn't help but think "arbitrary" a bit off. (for an interesting article on the relevance and irrelevance of line breaks, check this out: "The End of the Line for Modern Poetry")

Thus, "Wing," in which Williams appears to use line breaks for at least two distinct purposes—to ease readers through the familiar, to enjamb us into the uncomfortable—becomes a useful tool for demonstrating the purposeful use of line breaks.

In "Wing," Williams writes about two distinct types of experience. The first is the reliable and familiar, the factual if you will; the second is the suddenly new and, therefore, unfamiliar. For the former she uses an endstopped line, the latter an enjambed one. By line 2 of the poem, she's used both:

People can remove themselves from us.

I don't mean death. I mean another

undeniable turning, like a wing

we never noticed suddenly swinging

open, visible in ways only we see:

Although a bit enigmatic for me at first, line 1 is pretty straight forward: people can get up from the table, they can return to their cubicle, to their barstool. They can move away, and they can die, which is what Williams writes in line 2, though her speaker (whom it's fair to say is the poet) says that isn't what she's talking about. She's talking about "another / undeniable turning." That period at the end of line 1, and that after "death," kick off the poem with something readers can rely on, that they already know is true. Thus, an endstopped line, which reads like a sentence and poses no threat to our eye nor to our mind: we're given single, easily digested thoughts that end with what we expect, a period: "People can remove themselves from us. / I don't mean death." Okay. No problem.

That first enjambment on "another," however, is not so digestible because it breaks the clause where we don't expect. It wrecks the complete thought by breaking the clause—"I mean another / undeniable turning"—in half. She's talking about something else, and this else is not a comfortable other to consider, seeing as how the relationship has gone bust. Had the first two sentences not been consistent with their language and pattern, perhaps this enjambment wouldn't have such an effect, but they are consistent.

The language shift here reiterates this change and enforces the effect of the enjamment. The first two sentences are comprised of arrhythmic mono- and bi-syllabic words. The sentences are short, over and done with in one line or less. The third sentence, in which that first enjambment occurs, stretches across four lines of the poem—five if we include what follows the colon. It quickly makes use of multi-syllabic words, "another" and "undeniable," and so its feel is different not only in the eye and brain but in the ear. The pace is slowed and musical for a moment. This is echoed at the end of line 4 with "suddenly swinging," a nice rhyme with the internal "turning" and, to my mind, a clear signal about the prominence of this other type of removal a lover, swiftly removed, feels. So, Williams uses several tools to emphasize the fact that change is coming, line break being but one of them and the first to do so.

In the middle of the poem, Williams uses a trio of endstopped lines that coincide with what we, the lover, think we can count on as "once included ones":

the mute, familiar angles of a face,

its histories we thought transparent,

its banks of flesh. A different glance

charged with some fresh need or ancient

But as soon as the lover encounters the shift from loved to unloved—"A different glance"—we're back to enjambment. It's sort of a. . .classic case of form meeting content and vice versa.

In contemporary poetry, the uses of line breaks run the gamut, and poets use them at great length to achieve desired effects—or not. The fact is that as long as poets are using lines, then line breaks are integral to the moves and meanings of their poems. Even arbitrary line breaks have an effect, so it seems to me that, for a poet, an examined poem is the one worth writing.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

It's 4:07 A.M.

Thursday, May 26, 2011

Ellen Bass' "Gate C22"

But I'm less concerned with the kiss and its voyeurs than I am with the simile in the poem's second stanza. Bass writes the lovers "kissed lavish / kisses like the ocean in the early morning." At first I was like — that's so dull, a missed opportunity, an okay image that falls flat because a kiss is nothing like an ocean and the simile does nothing to change that perception—has done nothing yet, that is.

I should say that I also found the poem neither here nor there at this point: strong imagery, strong verbs, but nothing that sucked me in the way that kiss sucked in its onlookers. The first stanza was fine, and the second began in a dull mode, using two short, flat sentences in a single line to start an "unattractive" description of the couple:

Neither of them was young. His beard was gray.

She carried a few extra pounds you could imagine

her saying she had to lose. But they kissed lavish

kisses like the ocean in the early morning,

Of course, those opening lines are a setup. Rather than stop that simile after a single line, Bass continues to work the metaphor, describing how the kiss/ocean "gathers and swells, sucking / each rock under, swallowing it / again and again. Drawing that comparison out over a few lines is extraordinary, allowing it a chance not just to be a comparison but a synthesis of the two disparate images. The verbs gather, swells, sucking, swallowing apply as well to the tide as they do to the embrace. It's a great example of why poets should be careful not to stop their metaphors short, but to work them out. They can always be pared back if that's what the poem desires.

The other thing I like about this kiss/ocean is that the simile really becomes the poem's center, even more so than the kiss. The kiss is the audience's central image, but not the poetry's. What I mean by this is that the description of the ocean not only sensualizes the kiss by being sensual itself but acts as something of a scaffold for the workings of the rest of the poem. Imagistically, it is the most sensual part of the piece—the literal descriptions of the kissers and their kiss don't come close. More importantly, the movement of the poem from stanza to stanza follows the movements of a tide, rushing in and easing out, extending at times with great velocity, others with a benign steadiness. This can be seen in Bass' use of mini-catalogues: each stanza begins with some scene-setting narrative, then dives into these brief but very imaginative lists, which, for me, is where the poem most succeeds. Bass' kiss/ocean, placed in the middle of the poem, seems to be the fulcrum on which this back-and-forth occurs. It becomes the center of the poetry and, for me, the imagination of the poem even though the kiss remains the center of attention.

I find the ocean a good central metaphor for "Gate C22" for another reason, too. The shoreline with its rising and falling tide is a place of gatherings and departures—the flotsam washes onto shore, the beach junk washes out. In and out, coming and going, landings and departures—it's an airport. How perfect!

I think the first person to really drive home to me the point of expanding a metaphor (remembering it can also be pared back) was Steve Orlen. We were reviewing some poems of mine when he commented that I had taken a just-okay image and turned it into something special by working it out over the course of several lines. I had been oblivious to this fact, but since then have made a point of looking to see how I and others use metaphor in our poems. For Orlen—at least in our conversations—it was often a matter of rhythm, growing an image in order for the language to keep up its music. But, as it does in Bass' poem, expanding the analogy can also give the imagination room to grow, infiltrating and invigorating the rest of the poem.

Sunday, May 22, 2011

Turning a Poem onto its Head

What I ran across was the start of a poem that centered on the star jasmine growing

in front of my house. For whatever reason, I'd wanted to write about that thing for weeks -- probably since it had fully burst into bloom -- and seeing my first go-at-it there on the page reminded me that I had yet to properly work up the idea. The problem was my opening lines stunk:

in front of my house. For whatever reason, I'd wanted to write about that thing for weeks -- probably since it had fully burst into bloom -- and seeing my first go-at-it there on the page reminded me that I had yet to properly work up the idea. The problem was my opening lines stunk:With its white cluster of tiny trumpet

bells, this jasmine lingers on the sleeve

I brushed against it, unknowingly

at first. . .

Now I liked (and have kept, at least for now) the image of the trumpet bells, the words linger and sleeve, but I disliked that ignorant word unknowingly and that flat, opening preposition With. I didn't care for the line breaks either. Creating no desirable effect of their own, they put the pace of the lines in too much conflict with the natural rhythm of the language. And none of the words received pause or attention because the rhythm was gangly instead of musical -- all of which I blamed on the line breaks, right or wrong.

The ensuing lines and few stanzas suffered the consequences of that sad opening and aren't worth discussing further. I liked a few of the sentiments that had turned up, however, a few of the jumps the poem made as it strove for new images and content. So, I made the decision to salvage what I could. The question was, how?

And the answer was to turn the poem onto its head, effectively starting where that initial string of ideas (it hasn't been accurate, really, to call them a poem) had ended -- the last line. Actually, the last line was "and they bloom, the silent speak." So, I restarted with the penultimate line, which I broke: "Drought pushes these loveliest of flowers / to the edge" and so on, working my way backward through the piece by every two lines or so, keeping what worked, dumping what didn't. Old connections were cut; a new logic formed. Even better -- whatever original emotional attachments I had to the jasmine and, thus, to the poem became severed by this new arrangement, allowing me to explore emotions and ideas that wouldn't have otherwise arrived in the poem's original form.

Sure, restarting a poem with the end is a bit arbitrary, but its effect -- the poem opens itself in a new way -- is not. Often that's the trick: to see the usual as unusual, the familiar as strange. As a writer and reader of poetry, I prefer not to know a poem's ending before I arrive at it -- the experience isn't surprising that way. But as the poet-in-process, I particularly enjoy not knowing how the poem is about to begin.

Friday, May 20, 2011

Aha! My new blog/website just went online.

Monday, May 16, 2011

Paula Bohince's "Nostalgic"

"Nostalgic" is a short, 3-stanza poem with lines that range from the short to the very short -- the clipped -- the briefest of which is the one-word last line of the poem, "cloud-headed," and the longest of which is the third line of the poem, "cloistered homage to a decade of geese." It is a lyric piece although I'm not entirely sure it doesn't tell a story of a leaving...from what I'm unsure. This could be a love (forlorn love) poem, as there is a "we" in it that definitely doesn't include me, and uses language like "kiss" and "departure" and "In the end," which taken together can suggest love gone awry. But I also wonder of environmental loss: the "robin's / blurred departure," the "homage to a decade of geese," "the marsh / where cattails remained when all else / left." The question is -- are these images meant to be read literally or metaphorically? Or both?

Bohince's clipped lines help create this sense of discontinuity. No pattern of consistent length emerges: some lines stick out, some don't. As well, many of the lines are so short they disrupt meaning. Whereas a poet like Billy Collins generally has a complete phrase or thought per line, Bohince breaks her thoughts up across lines in this poem such that rhythmic and cognitive flow are disrupted. Consider the last stanza:

In the end, we were landmark,

compass, same as the lingered-over

pond, the marsh

where cattails remained when all else

left. Ragged in salt,

cloud-headed.

All but two lines are enjambed in a way that disrupts immediate meaning-making, though in gestalt they do work together to create sense. Plus, Bohince has a few nice effects due to her enjambments. The way "lingered-over" hangs on the stanza's second line does make me linger a moment over the "pond" of the ensuing line. The tough enjambment at ". . . all else" slams an emphasis on "left," supporting the read that loss/departure are prime components to the story and theme of this poem.

And, the discontinuity of the lines adds to the poem's overall sense of melancholy, darkness. This mood, of course, is more obviously driven by some of Bohince's choice words: "haunting," "departure," "ragged," "cloud-headed." I would include "Un-find" in this list as well since it is such a weirdly formed word. "Un-find" makes me feel so uncomfortable. I mean -- that's an impossible task. Once something is found, can it be un-found? It can be lost, but can it be...ignored? Sort of like finding Waldo: once you know he's there, it's pretty well impossible to un-know his location, to un-find him on that page of the hidden picture book.

Perhaps this notion of impossibility is at the crux of the poem. There's this clear sense of letting go, of being ordered to let go, as evidenced by the commands in the second stanza, yet to feel nostalgic is generally an acceptable way to feel. It is bittersweetly pleasant. It is a remembrance and longing for a happiness that has been but is no longer. Perhaps the speaker here has been unable to move forward. Perhaps she feels fettered by those emotions and their connection to past events necessary to the poem but hidden from its readers. And if that's the case, then the poem actually struggles against it's title: the speaker does not want to feel this way.